Long-term contact, particularly with a person's skin lesions, is now thought to be the main method of transmission.

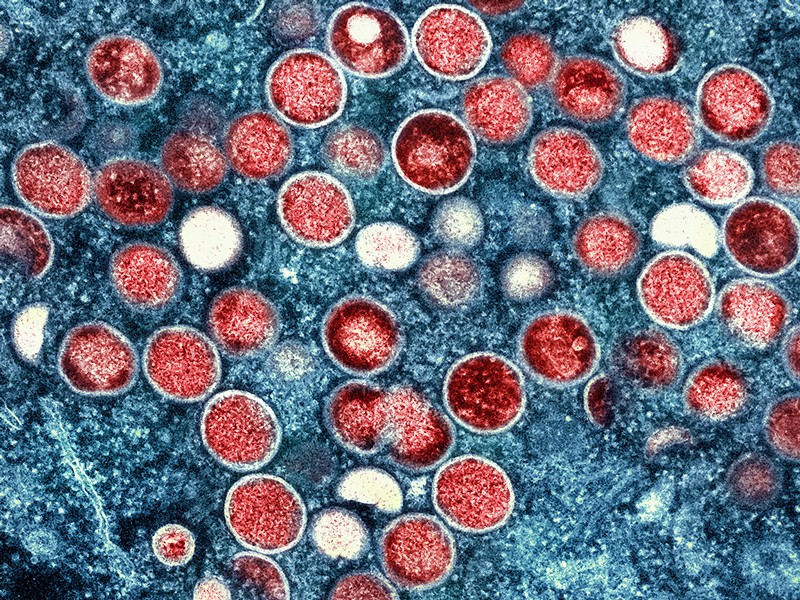

Infected cells are seen in blue in this coloured transmission electron microscope picture of monkeypox virus particles (red). Credit: SPL/NIAID/NIH

Researchers are learning more about the disease's transmission as the number of cases of monkeypox worldwide keeps rising. According to a number of recent research, early predictions that the virus spreads mostly through frequent skin-to-skin contact between individuals have largely come true.

According to Oriol Mitjà, a researcher in infectious diseases at the Germans Trias I Pujol University Hospital in Barcelona, Spain, who co-authored one of the recent studies published in The Lancet1, "When you put all these studies together, we see that the clinical presentation everywhere is similar—but also surprising." This is due to the fact that the signs and symptoms are different from what scientists had seen in West and Central Africa, where the monkeypox virus has been responsible for sporadic, long-lasting epidemics for decades.

Since early May, monkeypox has infected more than 32,000 people in more than 90 countries, with roughly one-third of those illnesses occurring in the United States. The rapid spread of the virus prompted the World Health Organization to declare its highest public health alert on July 23. US President Joe Biden followed suit by announcing a US public health emergency on August 4.

The majority of cases have so far involved males who have sex with men (MSM), particularly those who have several sexual partners or who engage in anonymous sex, despite the fact that some women and children have been infected since May. According to Mitjà, the virus has undoubtedly used the MSM community's extensive sexual networks to its advantage in order to propagate quickly. The virus will have additional opportunity to infect other groups as it spreads, including wild animals, who might develop viral reservoirs that could repeatedly infect people, according to experts.

Teeming with virus:

Flu-like symptoms, swollen lymph nodes, and characteristic fluid-filled lesions on the skin can all appear in a person with monkeypox. Mitjà and his colleagues report that samples taken when a person is diagnosed from skin lesions contain much more viral DNA than those taken from the throat1. This is despite the fact that some researchers have hypothesised that the monkeypox virus could spread through respiratory droplets or airborne particles, similar to how SARS-CoV-2 does. According to Boghuma Titanji, MD, an infectious-disease specialist at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, who was not involved in the study, the lesions appear to be relatively "teeming with virus."

A number of studies2, 3, including Mitjà's, demonstrate that few people get the illness from a household member who is sick but with whom they haven't had sexual contact. This discovery, along with the information on viral load, leads Titanji to surmise that respiratory droplets and airborne particles are probably not the main means of transmission. If confirmed by more study, it may raise the question of whether individuals should remain in isolation for the duration of an infection, which may be challenging given that the sickness appears to take up to a month to cure, she says.

According to Jessica Justman, an infectious-disease specialist at Columbia University in New York City, specific information regarding how a person's viral load increases over time is still lacking. Although Mitjà and his colleagues found little viral DNA in samples taken from people's throats early in the course of illness, she speculates that viral levels may have been higher if samples had been taken later or even earlier. Such information, which the researchers is currently gathering in a follow-up study, would enable public-health professionals to properly advise sick persons on isolation and treatment.

Talking about sex:

It is currently unknown if monkeypox is sexually transmitted in the strictest sense, meaning that it may spread from one person to another by blood, semen, or other body fluids during sex. However, a number of investigations have discovered that weeks after infection, monkeypox virus DNA may still be identified in a person's semen2,3. Additionally, one research found an infectious virus in one person's semen six days after their symptoms started to manifest.

Even if the virus is sexually transmissible, it is unknown how significant a role this route of transmission plays in comparison to simple skin-to-skin contact or breathing in respiratory particles, both of which happen during sex. Knowing how long an infectious virus may survive in semen will be crucial if more research reveals it there. The fact that viruses like Ebola may linger in semen for months or even years after infection has hindered attempts to stop epidemics. The UK Health Security Agency advises people to continue using condoms for eight weeks after infection until additional study is done.

The researchers found that having more lesions in the mouth and throat was associated with oral sex, whereas having more lesions in and around the anus was associated with anal-receptive sex. Given all of these findings, Titanji believes it's imperative that public health experts discuss sex openly in their recommendations and be clear about the different methods of protection that are available.

There is a desperate need for more data from carefully planned trials, according to Justman. Given the revelation of limited vaccine stocks, unavailable antiviral medications, and poor testing, several researchers already worry that the outbreak is past the threshold of being stopped. Compared to COVID-19, she says, monkeypox research is less funded and less motivated. As there was a "Operation Warp Speed" to speed up US vaccine development during the epidemic, she continues, "We don't have one."

Comments

Post a Comment

Thanks You